About the UK Community of Practice Knowledge Production Series

This essay is part of the Liberatory Archives and Memory (LAMy) UK Community of Practice knowledge production series. Together, memory workers, artists, and archivists share reflections, research, and creative practices that reimagine archives as living, collective spaces of resistance, healing, and liberation.

Foreword

‘What I come across in the newspaper articles, doctor’s records, the infirmary register and even recent scholarship on Paul, are instances of relentless misunderstanding… these poems and experiments, then can only ever be a record of my search for parts of myself in the archive.‘ Remi Graves, Coal

The wrong vibe by Erinma Ochu

Why are you here? By Tosin Olufon

“Until the lions have their historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” Chinua Achebe, 1958

Finding solidarity by Nadine Aranki

From the belly of the beast

From the belly of the beast

You can say the least

They care about everyone

But your life doesn’t matter

Especially when you go east

If you talk about the empire

You need to be subtle

Who said anyone’s an oppressor?

No need to mention attacks then

No need to mention attacks now

‘Cause the new empire doesn’t see you now

Like it did not see your ancestors if

You looked back

I wonder who became a settler in Canada?

Who worked on erasing its Indigenous

People?

It’s too “sensitive” to say their name upfront

I wonder how children in Palestine lose their

Life?

It’s a mystery but hush hush

The murderers’ emotions will be hurt if you

say it blunt.

Often the alternative for me is to foreground Indigenous people and ways of life: to place that above the colonial archive. For one exhibition, I placed herbs alongside the colonial object, and invited audiences to smell them. Decolonising archives then becomes a way to decolonise the senses.

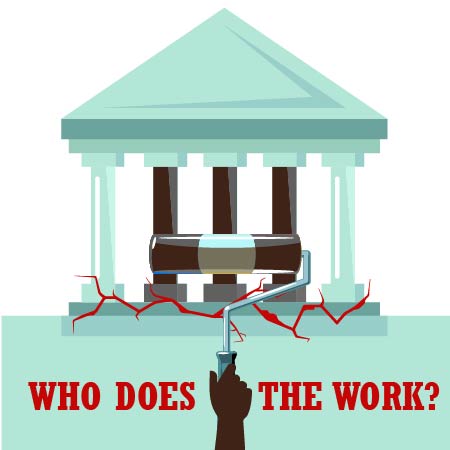

Whose knowledge counts by Abira Hussein

To exist in museums and archives, you have to be exceptional. These spaces are not easily accessible; conferences, networks, and opportunities may be open theoretically, but the routes are uneven, costly, and demanding. There are so few of us here, and those who are must navigate the weight of visibility and constant tests of legitimacy. My Somali heritage work has been shaped by long periods of unpaid labour. It taught me the contradictions of this space: having agency recognised and denied in the exact same moment; being expected to show gratitude for objects taken from our histories.

“The structural racial, class, and gender inequalities that exist within the museum echo the global structural inequalities born out of slavery, colonization, racial capitalism, and imperialism… Requests for the restitution of objects arise from a long history of dispossession that echoes extraction as a logic of racial capitalism.”

Françoise Vergès (2024)

These experiences are structural, not incidental. Job interviews and rejections are less about capability and more about whose knowledge counts. Community-held and lived expertise is often delegitimised unless reframed to fit institutional language. As scholar, Ramon Amaro observes, our presence is mediated by systems that decide what it can mean, even in digital form.

Glissant’s Poetics of Relation suggests another approach: opacity as a form of autonomy, relation without assimilation, recognising that what makes us unique cannot be fully understood. Perhaps the question is not how to better decolonise the archive, but how to stop trying and, instead, create spaces that belong entirely to us. An example of this is the Culture House in London, the first permanent Somali exhibition space, ‘presenting narratives of origin, displacement, migration, and new belongings’ within Somali culture and reconnecting British Somalis via community-donated objects and fostered by the Anti-Tribalism Movement. Another example is the UnMuseum, developed by the Black South West Network (BSWN) in Bristol. The UnMuseum aims to serve as a ‘decolonial reconceptualisation’ by empowering those whose stories have been marginalised or erased.

‘Ultimately, building for liberation is not a style but an orientation. It situates architecture within long struggles against empire and captivity, and calls contemporary practitioners to continue that lineage — to design not for control, but for the expansion of freedom itself.’ Amara Spence

We conclude that whether we are creating new museum spaces, breaking through or transforming existing or emerging systems, centering lived experience using creative tools that offer self-development and community building as a way to offer liberatory alternatives.

Nadine Aranki (she/her)

Nadine Aranki is a Palestinian curator, cultural worker, facilitator, coordinator and content producer based in London. She is a member of Brent Artist Network. Aranki has worked in the fields of culture, human rights, and education in Palestine and the UK. She is the author of the report ‘Conversations with Culture, Heritage and Tourism Actors in Palestine: Needs and Challenges within a Context of Extreme Military Violence’. With Meg Peterson, she co-curated The Many Lives of Gaza, a 2024 touring exhibition that has been shown in London, Birmingham and Norwich.

Abira Hussein (she/her)

Abira Hussein is a researcher and curator of Somali heritage, based in the UK. Her work explores how digital technologies, including virtual and mixed reality, can transform engagement with colonial-era archives and reconnect diasporic communities with their heritage. She uses participatory methods to co-create community-driven archival spaces, challenging dominant historical narratives and fostering inclusive, culturally rooted remembrance. Hussein has collaborated with institutions such as the British Museum, Barbican, and The National Archives. Her projects include the VR experience Coming Home (2017) and the Mixed Reality NOMAD project (2018).

Tosin Olufon (she/her)

Tosin is a Yoruba artist and researcher of Nigerian heritage. Her practice centres on reimagining African folklore for virtual reality and 3D animation, using immersive storytelling as a tool for heritage preservation. Through her work, she explores the possibilities of a decolonised immersive archive that resists static preservation and reflects the voices being represented.

www.tosinolufon.com

www.linkedin.com/in/tosin-olufon

Dr Erinma Ochu (they/them)

Erinma is a storyteller and biologist experimenting with collective consciousness as a form of earthmaking. Their poem ‘How to read the atmosphere’ was shortlisted for the 2025 Disabled Poets Prize. As Watershed’s inaugural Researcher in Residence they are enquiring into epistemic justice. They are Wallscourt Associate Professor in Immersive Media at UWE Bristol’s Digital Cultures Research Centre, a Stuart Hall Foundation’s Scholars & Fellows network alumni and storytelling champion on sustainable computing research initiative, NetDRIVE.

https://www.watershed.co.uk/studio/residents/erinma-ochu

https://www.linkedin.com/in/erinmaochu/

References

Abdi, S. (2025). ‘Artefacts were just sitting in suitcases in people’s homes’: the London museum preserving Somali culture. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2025/sep/02/artefacts-london-museum-preserving-somali-culture-house

Amaro, R. (2022). The Black Technical Object: On Machine Learning and the Aspiration of Black Being. London, Sternberg Press.

Carroll et al. (2018). The CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. Global Indigenous Data Alliance https://www.gida-global.org/care

Egbe, A. & Hussein, A. (2024) Prioritising community values and access. The UnMuseum Conference: Uncovering the Unseen, Understanding the Unheard. Presentation. https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/output/13420127

Grave, R. (2025). Coal. Monitor Books.

Glissant, E. (1997). The Poetics of Relation. The University of Michigan Press.

Harris R. & Bryant, P. (2024). Birmingham Museums Citizens’ Jury. Shared Futures.

Palmer, L.A. (2025). Heritage and Ephemerality: The Politics of Black Cultural Memory. https://whoseknowledge.org/

Popple, S. Mutibwa D. H., and Prescott, A. (2020). Community archives and the creation of living knowledge. In: Popple, S., Prescott, A and Mutibwa D. (eds). Communities, Archives and new collaborative practices. Series: Connected Communities. Policy Press: Bristol, UK; Chicago IL, 1-18.

Puente, G. & Muhammad, Z. aka White Pube (2019). Everything that is wrong with museums. NPU-konferansen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHf8qHNPZkk

Vergès, F. (2024). A Programme of Absolute Disorder: Decolonizing the Museum. Pluto Press

Spence, A. (2025). Architectures of Abolition: Imagining a built environment from carcerality to liberation. Substack: https://amahraspence.substack.com/p/architectures-of-abolition