A Conversation with Hala Al-Afsaa

26 July 2024, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Ezrena Marwan and Sally Alhaq, the co-leads of the Liberatory Archives and Memory (LAMy) programme, had the pleasure of meeting Hala Al-Afsaa, one of the co-founders of the Syrian Design Archive (SDA), during her time in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

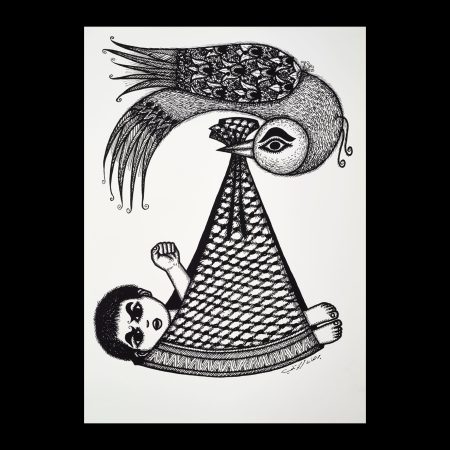

The SDA is a digital archive, documenting graphic design in Syria and the stories it tells. The SDA hopes to have a physical archive one day, where they can preserve the materials. They see themselves as “a living testament to the power of preservation, unravelling some of the threads that weave the fabric of our shared, yet very different and diversified, cultural and design heritage.” In the words of the SDA team, “Our adventure began in Syria, where we unexpectedly found ourselves amidst people’s bookshelves, old archives, and ancient bookshops places suspended in time.”

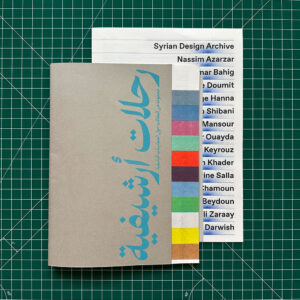

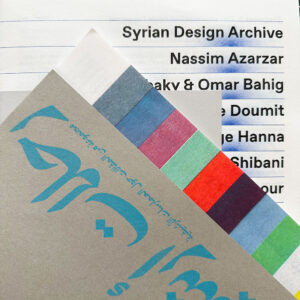

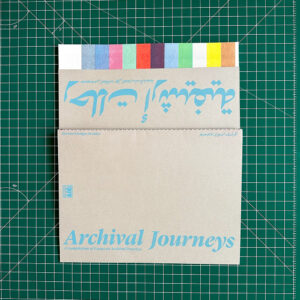

In this conversation, Hala reflects on the significance of documenting Syrian design histories and the urgent role of archives in preserving cultural memory amidst displacement and conflict. Hala also shares insights into their first publication, Archival Journeys: A Compilation of Essays on Archival Practices, which brings together eleven essays reflecting on the political and social dimensions of archival work through the lens of Syrian designers. Together, we explore the intersections of design, memory, and resistance.

Introduction

_

Ezrena: Hala, can you introduce yourself?

Hala: My name is Hala Al-Afsaa, I am 28, and I am one of the three co-founders of the Syrian Design Archive with my friend Kinda Ghannoum and Sally Alasaffen.

Sally: I happen to be in Kuala Lumpur and I’m very happy to be here. Very funny for a Syrian, and an Egyptian, to meet in Kuala Lumpur. It is not a story that I have heard of.

Hala: Yes, I know what you mean. We’re more likely to meet on social media than in real life in foreign countries.

Background to the Archive

_

Ezrena: Tell us a bit about the Syrian Design Archive and what you’re doing.

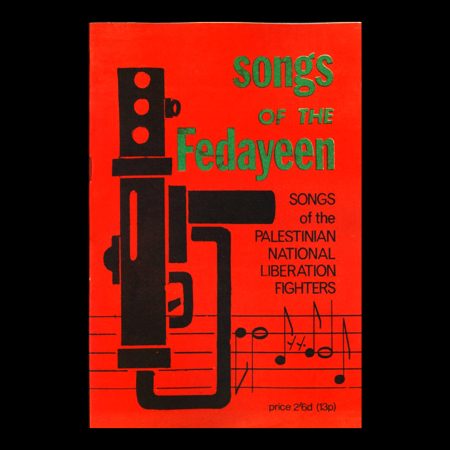

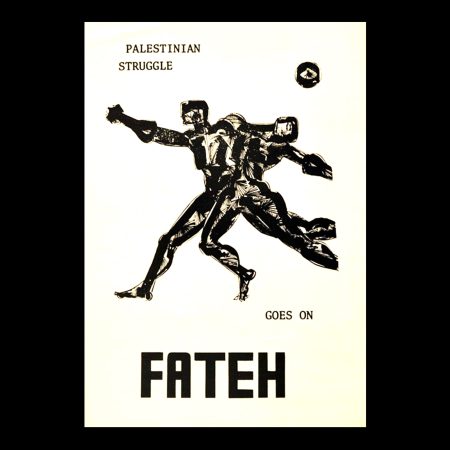

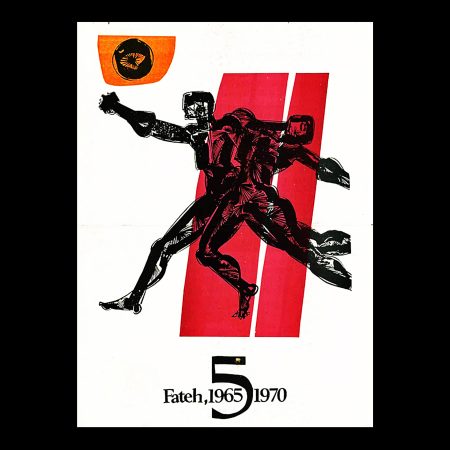

Hala: The Syrian Design Archive is a documentary initiative. It is mostly digital at the moment. We archive all the graphic design and typography found in Syria. And we try to republish this old data through new media, on social media. We picked social media because of how fast the image travels and how it reaches a lot of people that are interested in design or research or Syrian heritage in general. So the Design Archive actually has five sectors; The Syrian Stamp Archive, Syrian Media Archive, Syrian Print Archive, and Syrian Type Archive. Each has an individual account. So they’re all individual pages, and there’s an individual page for the Syrian Design Archive itself, where we post the conferences and interviews and features and publications and stuff.

Ezrena: This is amazing. What inspired all of you to start this archive?

Hala: During COVID, there was a wave of Arabic archives that popped up on social media. People would take it as a hobby to document signage, when they walk down the street, such as typography or lettering of like, old artists. We all, I feel, got nostalgic towards Arabic calligraphy and letterings all of a sudden. And I think it started from there. Also, my friend Kinda, the other co-founder, was doing her master’s in Belgium and she wanted to do something that connected to the Arab identity, especially that most of her colleagues were doing Western topics. She wanted to do an Arabic typography kind of piece, and she wanted to research Syria and implement a Syrian graphic design or typography. To realize that there was a gap, she didn’t find anything. So yeah, that’s when she decided with the trend going on. She was like, why don’t we start a Syrian Design Archive?

And then we started, she contacted me and Sally Alassafen, because as designers, we have an eye for this thing. And Sally is already one of the people that likes walking in the street and taking photos. And for me, I’ve always loved graphic design, my family has a very large library, which I always like to read from and post on social media. We all got together and we started really small. The first thought was, let’s book this handle, the Instagram handle. And then, we set up an email and we started and we never expected where it would go. And we’re actually looking back at three and a half years. It went too far. There’s a lot of things happening for us. The archive has been featured in a lot of other pieces, and we have seen our vision come to life. Because we wanted researchers, when they search about Syrian graphic design, to find data to work with. So yeah, that’s it.

Ezrena: That shows the gap in history that we have. And then once you start to fill the gap, there’s so much, because it’s something that everyone needs. And that you, because you just started– everyone’s coming to you.

Hala: Yeah, like rushing.

Archiving within Syria/within Protest

_

Hala: Most universities in Syria, when they teach graphic design or any kind of typography, they use Western or European sources, books and designers. That’s why we’re very disconnected from our identities, we’re always trying to be someone else. And the thing is- because of the war, all the data is already very endangered. It’s either bombed or burned or flooded. And the government doesn’t really take action on that, because I think there are bigger issues at the moment. And yeah, so we felt it is kind of our responsibility as designers. I think it affects us very much, that we’re no traditional archivists, that we are actually designers that are archiving design material. We look at things with more appreciation and we value the material more. We also think the most important thing is that there’s a lot of material, but also even for us, there is a limitation– we don’t know where to get the credits. We have a lot of beautiful designs, but to this day we don’t know who the designer is, where to get the information from. Because we either track down their families or if they’ve work in television, we’ve tried multiple times to speak to the TV industry, but most of the archives are actually not available to the people. The archives are secretive.

“We have a lot of beautiful designs, but to this day we don’t know who the designer is, where to get the information from.”

Sally: What are you looking for? What personal passion in design are you tracing back to Syrian history?

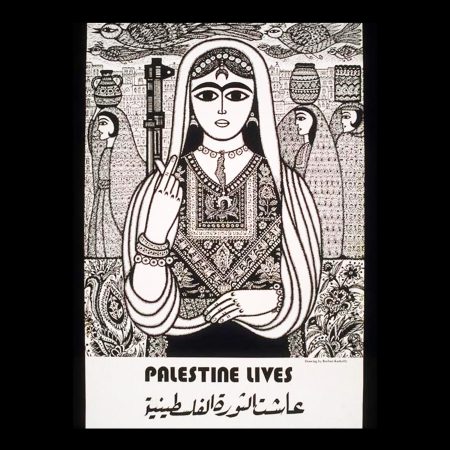

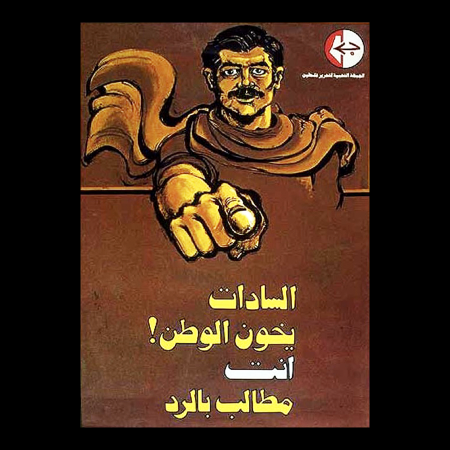

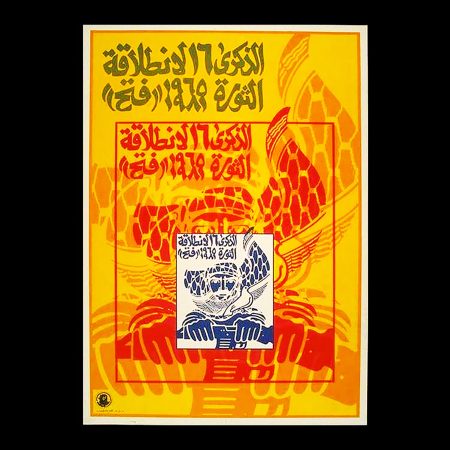

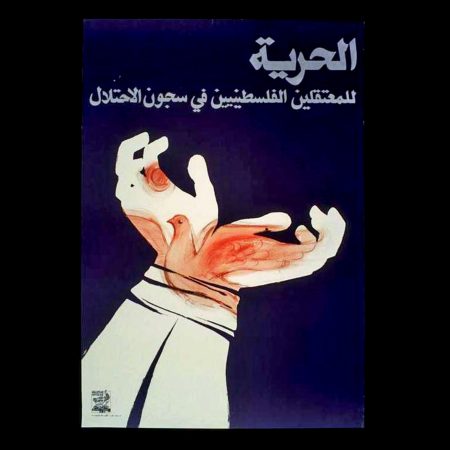

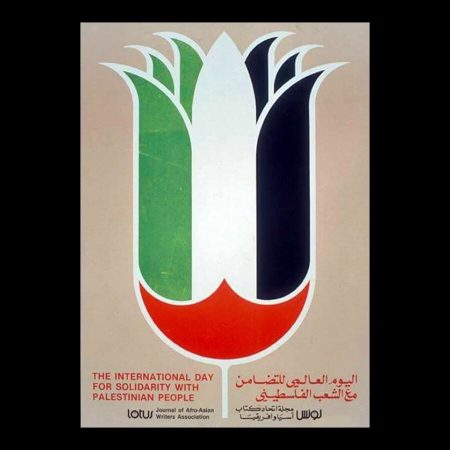

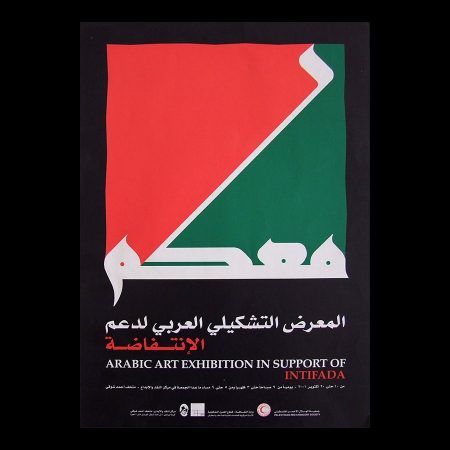

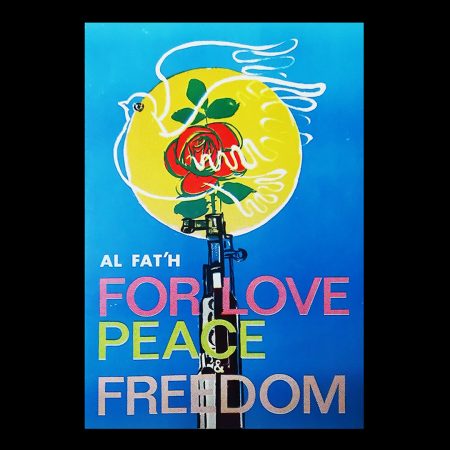

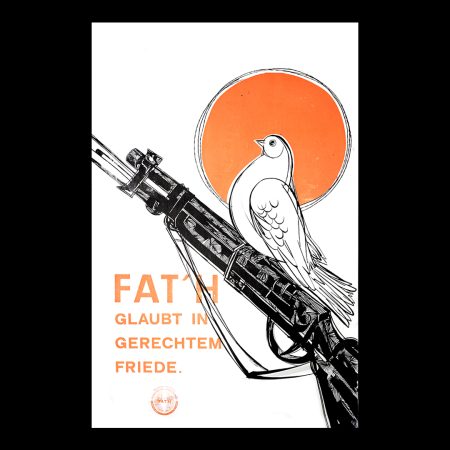

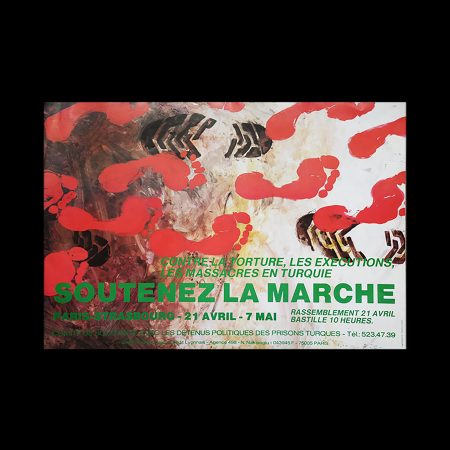

Hala: For us in the archive, we’re kind of trying hard to highlight that we existed. You know what I mean? – In the graphic design world, we’ve made a difference. We’ve set a trend at some point. We’ve set an example. It hasn’t always been the myth of the European as creator and savior. You know what I mean? Because all our narratives- most of the countries that are not first-world countries got influenced by this myth. Like Ezrena said, the narratives are silenced. And they’re trying hard to diminish most of the narratives. So I think the thing that’s important to us is to prove that there is a narrative. And it’s worth looking at and exploring. Because there’s a lot of things, even after the war, they will try to convince you certain things didn’t happen. But actually, just by looking at art or graphic design, you can know things have happened. Because designers have created a response through visuals. So why would a designer create a poster for a protest if there was nothing to protest for?

Sally: I remember for years and years, I would use this photo from a certain protest in a Syrian town in 2011. It said, something like– down with everything. I think it was from a very specific spot in Syria (Kafr Nabl), where it was sort of the heart of the resistance. And I think in a way, such a simple photo that was circulating all over Facebook made all the revolutionaries around the world say, this is coming from the heart of Syria right now, and it represents us politically. And I think there is something so special about what was produced in a protest. It is not trying to force something, it is just naturally felt. And you feel it in your heart. Like, yeah, this happened. It is just as simple as that.

Hala: I think protest art is the most interesting art. Because it is kind of advocating, but at the same time, it’s kind of non-violent. You know what I mean? So it’s kind of a bit of both. And also, the visuals, like you said, relate to a lot of different scenarios in the same MENA region. Because the culture is similar. The way people lead countries are very similar.

Sally: There was a sense of humor in it. And there was everything in very, very difficult moments. People just used everything to say that we’re alive and we’re doing this.

Decolonial Practices in Engaging with the Archive

_

Ezrena: Do you also look at government posters?

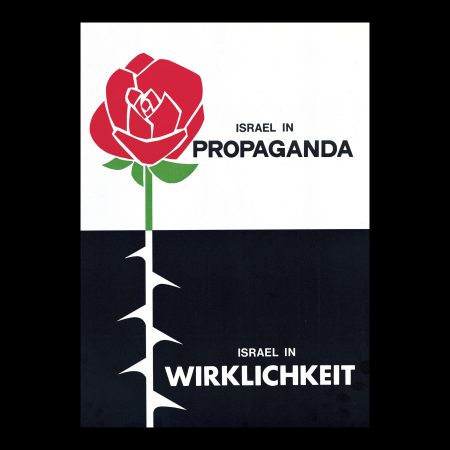

Hala: The one from today or back then? We actually also archive it. Because we feel as archivists, it is not our place to favor material. It is our place to just lay down and archive material. How is it falling down in a historic timeline? When you map out the visual material, you can actually map out the history, including its ups and downs. And revolutions. And wars. A lot of things. It is like creating a visual map in front of you. It will allow you to see even the patterns that are happening over and over again in the country. We actually archive a lot of things. There’s a library called Al-Assad Library in Damascus. It is huge, it has a lot of ancient data. We weren’t allowed to scan any of it, we were allowed to take pictures from behind glass frames. Any country that doesn’t want you to know something will not allow you into their archive. The fact that they have an archive, they already know that some narratives or some documents are important. That may come up in the future. And they’ll have to use them. I don’t know. I just think about that a lot. If it’s not valuable to you, why won’t you let people access it? What information do you not want people to know?

“When you map out the visual material, you can actually map out the history, including its ups and downs. And revolutions. And wars.”

Sally: It seems like the whole system is built for us not to know. I think in this region, the more we know, the more trouble we are to them. We have given them enough trouble back then. I think about what I hear from Syria; you said something about the fact that they don’t care about what is happening to the artifacts. Is it the same with museums? Are artifacts being looted?

Hala: It’s trafficked.

Hala: Yeah. I see a lot of influencers or people on social media. They go to museums, and the artifacts are Egyptian or Syrian. And they take a picture with the stuff from their country. But the museum is in, like, England or Europe. And they’re like, oh, okay. Here is where our heritage is going. And we always complain that we want to be decolonized. I feel like we’re not taking enough action.

Sally: You are taking action.

Hala: I am.

Hala: We are. But I feel people just need to step back and rethink.

Barriers to Archiving

_

Archival Journeys: A Compilation of Essays on Archival Practices

Sally: Can I say that government institutions are never going to produce something as pretty as this zine- What is the security situation like?

Hala: Yes, my friend Kinda was like, do you have to check security? Because in Syria, if something is a file in your name, they won’t let you enter. Or they’ll just jail you on the spot. So she’s like, can you run a security… I don’t know the term in English. A background check on your name. Just see before entering. After we did this. It was launched only two months ago, but you never know who read it. So we’re really scared.

Hala: And we’re always like, there’s a lot of steps we’re scared to take because our families are still there. And we never know the consequences of something. Like a certain sentence or a certain fact or a certain thing that would just trigger someone.

Sally: And in Syria, by your family’s name, you know which city you’re from, right?

Hala: Yes. There’s not a lot of names that are similar. So if my last name is Afsaa, for example, there’s no other Afsaa in the whole Syria. They know how to get you because they’re not going to be lost. You’re very identifiable.

Learning From Others

_

Hala: We’re trying, we’re not traditional archivists. We listen to talks or meet people like you guys. We always try to see how they’re doing things. Like you said. Like, talk more about practices with each other. We’re just learning along the way.

Ezrena: I really love that there’s this sort of, like, designer uprising happening. Yeah. In, like, Southeast Asia. In, like, the MENA region. I just love it. Because, the designers are really, really, really realizing, like, the power that they have to make change.

Hala: Yes.

More Barriers/Risks

_

Ezrena: But it’s also living in fear, right?

Hala: Yes.

Ezrena: Because you’re doing the work that fits.

Hala: Yes. That’s true. Because there are a lot of limitations. There are actual dangers. If you read my texts in the zine. There’s a lot of stuff that happened that I’ve written.

There are just certain encounters with– the government or the people. Or even, the business behind archiving. Like, bookstores that would actually have very, very, very powerful and valuable material. But once they know that you’re an archive. And we actually, we try to communicate with them that we’re just an initiative, we’re not an organization. And they just start to just say numbers that we can’t even begin to imagine of, like, the price of a document. Even for a scan. Someone wanted $300 per scan, per page. They think we made thousands, and we’re kind of tricking them. And we swear we’re not.

Sally: Which one is your text?

Hala: So, they’re color-coded here.

Sally: Oh.

Hala: So, these are, like, the colors of my text.

Sally: So cool.

Hala: Sure. Yeah, we love this design.

Ezrena: It’s beautiful.

Four Years of Archiving Syrian Designs

_

Ezrena: When did you guys start the archive?

Hala: Oh, the archive is three, it started in August 2020.

Ezrena: Okay. So, it’s about four years.

Hala: Yeah.

Ezrena: Okay. Four years old. Wow, really amazing.

Hala: Yeah.

Ezrena: Really amazing.

Hala: I was telling her three and a half years. I just realized it’s really four years.

Connecting in KL

_

Sally: But also, how cool is it that you have made something so cool out of being in Malaysia? It takes so much determination to– you know– make a place work out for you.

Hala: Yeah. I try to meet a lot of people. At first, I was a bit set back because of the cultural differences.

Sally: Right.

Hala: Because I needed it, not as Hala. I think it is the same for anyone from my region that comes here. Here everyone is so calm. You know? It is like Arab energy is not here, right? So, you need to kind of adapt.

Ezrena: What’s the Arab energy?

Hala: Anxious energy. Like. Haha.

Ezrena: Really?

Hala: Yeah, very! Like, hyper! Haha.

Sally: Yeah. Haha. Every time, I exaggerate in my jokes, and Ezrena is like, do you really mean this? I’m like, no, I’m sorry, I’m exaggerating. Haha.

Hala: I think it’s like Arab energy is, like, overdoing everything.

Sally: We’re overdoing it.

Hala: And being loud.

Sally: Especially, like, in sarcasm. Like, oh, my God, we’re so dramatic.

Hala: Yes, yes. And everyone here, you know, everyone I met, they’re like, calm down. Are you okay? I just, yeah, yeah, it’s me.

Sally: That’s just me. That’s my culture, huh? Haha.

Hala: Yeah. Everyone here is so peaceful and so calm. And I think it is very beautiful, actually. But also, everyone is open about their practice. I never saw anyone here gatekeep something. Which is something we have in the Arab world. People that reach success, they will often not tell you how they did it. Because they want to be the ones who stand out in their community. Here, I was afraid to ask at first, because I felt like it would be the same. But actually, people are so friendly. Even designers I have never met. But they are on my Instagram account. I ask them about stuff in the DMs and they just are very happy to help.

The team behind Syrian Design Archive

Kinda Ghannoum is a Syrian-Polish graphic designer with a background in architecture. Growing up in an artistic family in Syria, she developed a deep appreciation for art, design, and Arabic calligraphy. She later shifted her career to graphic design, becoming a self-taught designer before earning a Master of Visual Arts from Sint Lucas Antwerpen. Her work focuses on branding, typography, and research, drawing inspiration from Arabic typography and cultural heritage. She has collaborated with international entities and organizations, and she co-founded the Syrian Design Archive. Kinda’s approach is deeply influenced by her Syrian-Polish background, blending elements from both cultures in her design practice. She explores typography as a storytelling tool, using letterforms and patterns to communicate identity, memory, and cultural narratives. Her work often connects Eastern and Western design influences, creating a dialogue between tradition and modernity. Through this fusion, she challenges stereotypes, preserves heritage, and reinterprets cultural symbols in contemporary contexts. Instagram handle: @kindaghannoum

Hala Al Afsaa is a Syrian designer and activist who majored in architecture, she changed her path from architecture towards a visual communication and graphic design career, later on she obtained her MA degree in Visual communications and Media from Malaysia, having a deep interest in Arabic typography, illustration, and exploratory research projects on collective things that make us human, and a Co-founder of the Syrian Design Archive a non-profit documentary project, which archives examples of Arabic typography and graphic design. Instagram handle: @hala_alafsaa

Sally Alassafen, is a Syrian architect based in Damascus, She holds a Diploma degree in Architecture from Damascus University. She was born and raised in Damascus. Although no one in her family pursued a career related to art, growing up she was always surrounded by art supplies, creating paintings, or sculpting with clay. Sally always had an eye for Arabic type on the streets and a passion for photographing old signage on the streets of Damascus. Currently, she is working as an architect at an architecture studio in Dam, the Netherlands. Instagram handle: @sally_alassafen